Pat, our Kilmainham Gaol tour guide, pointed towards the damp tricolour, animated by gusts of bitter March wind whipping across the Stonebreakers’ Yard.

“Green is the colour of the Republic,” he explained. “Orange symbolises the Protestants and white represents the hope for a lasting peace between the two cultures in Ireland. This is the birthplace of modern Ireland.”

Visiting Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin – Europe’s largest unoccupied prison – is a journey into Irish Republican history.

This national monument is the site of the incarceration and execution of some of those who fought for Irish freedom, most famously the key players of the 1916 Easter Rising. This is their story and the dominant narrative running through a tour of this Dublin jail.

Kilmainham Gaol Tour & Its History

Visiting Kilmainham Gaol is a moving and evocative experience. Its tour is highly informative, and the stories told are haunting, from those of famous political leaders to those of ordinary citizens.

As a journey through Irish history, a Kilmainham Gaol tour is hard to beat.

The Great Famine

When Kilmainham first opened its doors in 1796 as the county gaol for Dublin, it was conceived as a new reform prison, advocating and fostering reform through a harsh regime of discipline and fear.

Conditions were grim. Up to five prisoners were incarcerated in one cell, just 28 sq. meters in size, with a single candle as the only source of heat and lighting. The windows lining the narrow corridor had no glass, granting the cells’ inhabitants the benefits of ‘therapeutic’ fresh air.

These early prisoners included women, who were incarcerated at Kilmainham Gaol until it became an all-male prison in 1851. Children too. Arrested for petty theft, the youngest reported prisoner was seven years old.

The Great Famine (1845 – 1849), caused by the blight of the potato crop, increased overcrowding at Kilmainham Gaol. The potato was the staple diet of the Irish people and, rather than die of starvation or an associated illness, some people resorted to deliberate incarceration in the quest for free food. Prison catering depended on the class of prisoner, but a typical meal comprised oatmeal, bread and milk.

Overcrowding was amplified by the Vagrancy Act of 1847. Intended to rid the streets of the unwashed poor, it resulted in swamping the gaol with those arrested for begging.

Kilmainham Gaol & the fight for Irish independence

Kilmainham Gaol is better known for – and is symbolic of – the fight for Irish independence. The leading figures in every rebellion against British rule since 1798 have been detained here.

Henry Joy McCracken, imprisoned in 1796, was the first in a long list of political prisoners incarcerated in Kilmainham Gaol. Seven years later, in 1803, Robert Emmet’s failed rebellion against British rule led to his incarceration and public hanging. His speech from the dock threw down the gauntlet to future generations of Irish nationalists:

When my country takes her place among the nations of the earth, then and not till then, let my epitaph be written

Robert Emmett

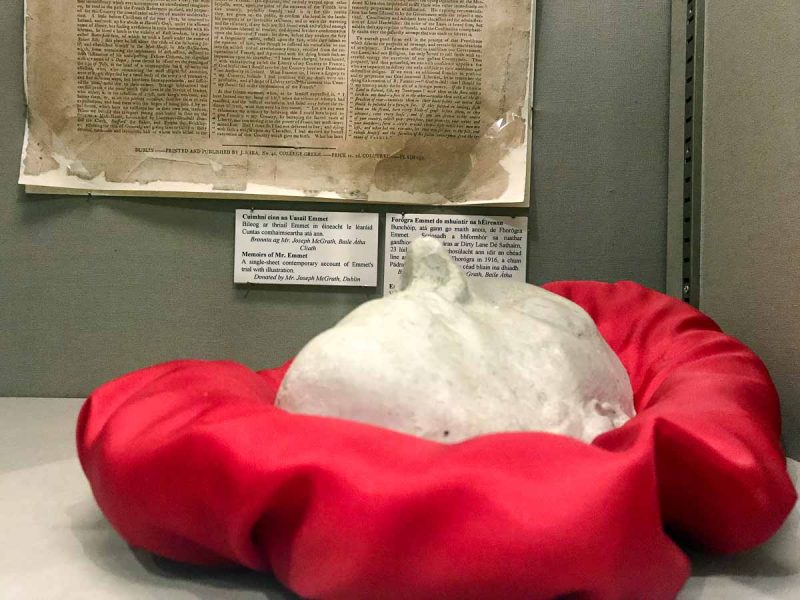

Robert Emmet’s death mask can be seen in Kilmainham Gaol Museum.

The 1916 Easter Rising

The most significant rebellion against British rule, particularly in symbolic terms, was the 1916 Easter Rising, whose leaders were incarcerated in Kilmainham Gaol’s so-called 1916 corridor.

On 24th April 1916 (Easter Monday), Patrick Pearse read out a proclamation from the steps of the General Post Office (GPO), declaring Ireland to be an independent republic. Over the next six days, around 1550 men under the command of Pearse, and a further 220 led by James Connolly of the Irish Citizen Army, seized control of strategic buildings in central Dublin.

Hopelessly outnumbered by around 20,000 British soldiers and facing overwhelming odds, the rebels eventually surrendered. 97 rebels were condemned to death under martial law imposed by the British Army. Fourteen of these were executed by firing squad in the Stonebreakers’ Yard at Kilmainham Gaol.

Poets and teachers and dreamers

The fighters of the 1916 Rising have been cast into the roles of romantic heroes, seeking Ireland’s freedom through self-sacrifice. In the words of Pat, our Kilmainham Gaol tour guide:

These were not military men. They were poets and teachers, men and women, dreaming of a new Ireland

Take Countess Constance Markiewicz, who hailed from an Anglo-Irish family in County Sligo and was married to a Polish Count. She became involved in the Irish Cultural Movement and took part in The Easter Rising as a member of the Irish Citizen Army.

Her death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment and she was transferred to Aylesbury Prison in England. On her release in 1917, as part of a late amnesty, she became the first woman to be elected to the House of Commons.

However, Countess Markiewicz never took up her seat. Instead, in 1919 she established an Irish political assembly, Dáil Éireann, with similarly elected compatriots.

Some of these rebel leaders left behind wives and children.

Countess Markiewicz’s commander, Michael Mallin, was not spared the death sentence. Executed by firing squad, he left behind a pregnant wife and four children.

Joseph Plunkett was another leader of the 1916 Easter Rising. Seven hours before his execution, he married his fiancée, Grace Gifford, in the prison chapel. Two British soldiers acted as witnesses.

After the ceremony, he was taken back to his cell, leaving his new wife behind. Grace never remarried.

East Wing of Kilmainham Gaol

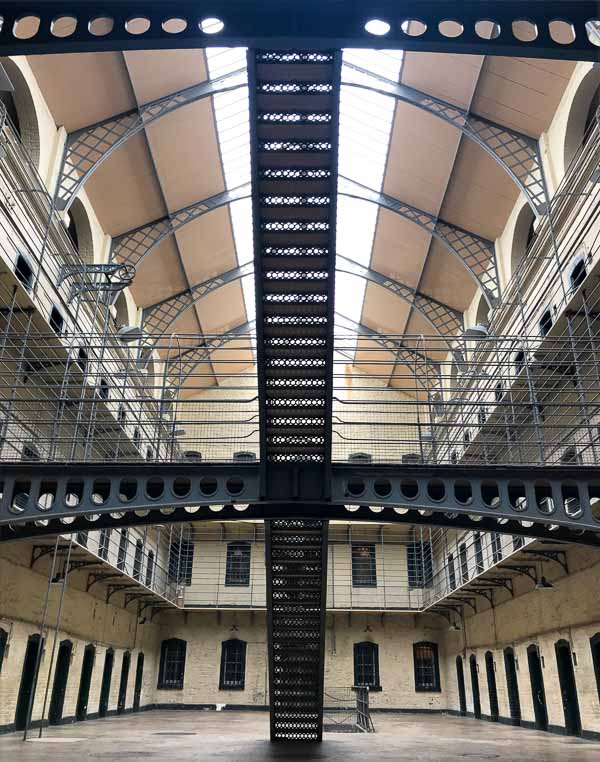

Leaving the Easter Rising and the 1916 corridor, we reach the East Wing of Kilmainham Gaol.

The Victorian era was the golden age of prison building and their design was underpinned by two principles: separation and inspection. The separation of prisoners broke up communities of corruption and vice, leaving an isolated inmate exposed solely to the reforming influence of prison staff. Inspection allowed prison guards a greater level of oversight.

In 1861, Kilmainham Gaol was extended and modelled on these principles.

Echoing Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon – “the all-seeing eye” – prison guards could keep watch on all prisoners incarcerated in 96 single cells. The narrow corridors were gone and in their place were catwalks in a vaulted space with an enormous skylight.

The fate of Kilmainham Gaol

Kilmainham Gaol finally closed its doors in 1924. Éamon de Valera, who would go on to be the president of Ireland, was one of its last prisoners.

For many years, the building was left to fall into ruin, shutting its doors on a painful period of Irish history. But time heals, and in 1960 a Board of Trustees was established to restore the gaol as a national monument.

Today, Kilmainham Gaol is also used extensively as a filming location. In The Name of The Father, Michael Collins, The Italian Job (one of the best movies set in Italy) and, more recently, Paddington 2 are among the films shot there.

And Dublin’s favourite sons, U2, shot their 1982 single A Celebration here.

The legacy of the Easter Rising

Visiting Kilmainham Gaol leaves you in no doubt of the self-sacrifice of the rebels, whose actions were a turning point in the birth of modern Ireland. In particular, the 1916 Easter Rising had a profound effect on Irish history and is embedded into the national psyche of its people, amongst whom I count myself.

However, the Easter Rising has its critics.

It left a 10-month war of independence and a brutal civil war in its wake. And it is sobering that violence succeeded where politics had failed.

Although a political outlier, John Bruton, the former Irish Taoiseach, suggested the Easter Rising had “damaged the Irish psyche” and “led directly to the violence experienced subsequently”, arguing that the events of 1916 have been used to justify violence in later years. Some critics argue that the rebels had no democratic mandate.

However, equally, the British did not have a democratic mandate to govern Ireland, maintaining control by force. For its part, the UK has never apologised for the actions of its army in quashing the uprising.

How to Get to Kilmainham Gaol

Kilmainham Gaol is located on Inchicore Rd, Kilmainham, Dublin 8, D08 RK28. The entrance is through the former Kilmainham Courthouse.

Kilmainham Gaol is a 15 – 20 minute walk from Dublin Heuston mainline station. The route is clearly signposted.

It is served by the Luas Red Line. The nearest stop is Suir Road.

Dublin Bus routes: no. 60 from Wellington Quay or Heuston Station, G1/G2 from Spencer Dock or Wellington Quay stop close by.

Kilmainham Gaol does not have a car park. Parking is available at the nearby Irish Museum of Modern Art/Royal Hospital Kilmainham. From here, it is a five-minute walk to the Gaol via West Avenue and Richmond Gate.

Tours and Tickets

The gaol is open for visit by guided tour only. Your ticket includes admission to the museum.

You can visit Kilmainham Gaol throughout the year. Opening hours are seasonal which you can check here.

As this is a popular attraction, I strongly recommend pre-booking online to avoid disappointment. Tickets can be booked 28 days in advance.

Cancellation tickets for the day are released online every morning between 9:15 am-9:30 am.

Tips for Visiting Kilmainham Gaol

- The tour of Kilmainham Gaol takes around one hour. I highly recommend setting aside a further hour to visit the museum, which is adjacent to the gaol and is arranged on three levels.

- No food or drink, except still water, is permitted. Gum chewing is also prohibited.

- Photography is allowed throughout the tour but video and audio recordings are not permitted

- Dress warmly. Parts of the tour take place outdoors but it can also be cold inside the gaol.

About Bridget

Bridget Coleman has been a passionate traveller for more than 30 years. She has visited 70+ countries, most as a solo traveller.

Articles on this site reflect her first-hand experiences.

To get in touch, email her at hello@theflashpacker.net or follow her on social media.